Size Matters: Unpacking the Debate on Expanding the Size of the Supreme Court

Is Nine Fine, or Is It Time We Redefine?

My Dad has often made the observation that as humans, we enter the world carrying with us an assumption that everything has always been the way it is now. And he’s right. From the moment we are able to form conscious thoughts about our surroundings, we seem to hold an inherent belief that the situations, institutions, and people around us have perpetually existed in their present form, timeless and immutable. And this presumption—that the world as we know it has forever existed in its current state—fosters within us a reluctance to embrace new possibilities. Instead, it is in our nature to resist change and cling tightly to what is familiar. But while this inclination to keep things as they are may have evolutionary benefits, it can hinder progress for adults in the modern era. In a society that is arguably evolving ever more rapidly than any other we have seen in recorded history, often this preference for the status quo mires us in stagnation, preventing us from making rational decisions and moving forward.

Taking the Easier Road: Psychologically, We'd Rather Stick than Shift

So, why do we do this? Why are we so resistant to change? Because it is easier not to change. While we typically give humans the benefit of the doubt, assuming they will act rationally to optimize their well-being and pursue their best interests, reality often unfolds differently than we might expect.

Despite our intelligence, the human mind operates within limitations imposed by its own finite processing capabilities. Intentional thought requires effort, which draws on a limited supply of cognitive resources—or mental energy—that is depleted with use. Metaphorically, the capacity for profound thought and other cognitive functions can be likened to a finite reserve of cognitive 'fuel'[1] or mental energy used to power various mental processes, which refreshes (or ‘tops-up’ the tank) with rest. In order to engage in any cognitive process, we must have sufficient mental energy to do so, and the more effort or energy a task requires, the more of the person’s cognitive resources are depleted from the collective “stockpile” of energy. Rational and deliberative thought, which are essential for careful examination of our circumstances and the abilities to anticipate and prepare for change, demand significant effort, thereby straining our limited stock of mental energy resources.

Basic human instinct is to conserve this energy until it is needed. The Principle of Least Effort tells us that [without a compelling outside motivation] a person will not expend more energy or effort than is necessary[2]. If there are two ways to achieve a goal, a person will opt for the one requiring the least amount of work. Our brains are hardwired to conserve mental resources and prioritize efficiency; as a result, rather than consistently opting for the most rational course of action, we often choose the path of least psychological resistance.[3] Thus, one explanation for our resistance to change is the contrast between the brain’s inclination to conserve cognitive energy resources, and the demanding nature of deep thought needed for embracing change.

Adjusting to change requires cognitive effort in a number of ways: adapting to new circumstances engages cognitive processes such as learning, memory, attention, flexibility, and emotional regulation—all of which demand and use mental energy. Making conscious changes to our behaviour necessitates deliberate effort and self-control. Adapting to change also often involves unlearning outdated patterns, which likewise demands mental effort. In order to accommodate new information or ways of thinking, effort is needed to modify or reconfigure the existing mental frameworks upon which our beliefs and habits were built. Navigating unfamiliar situations, making decisions with incomplete information, and contending with unpredictability, all demand additional mental energy and thereby deplete cognitive resources.

Change can also introduce uncertainty and ambiguity, potentially triggering emotional responses such as fear, anxiety, or discomfort. Managing these emotions necessitates mental energy and self-regulation which can be mentally taxing. Doubt leaves us adrift in unease, yet when we believe we possess a firm grasp on the world around us, we experience a sense of control that is both comforting and empowering. A sense of certainty in our beliefs offers an anchor in an unpredictable world. When we feel sure of something—when we know it to be real and unchanging—we indulge in the soothing fallacy that our surroundings are stable and dependable. It is therefore no surprise, then, that we are drawn towards the familiar, the certain, and the known, both because it is easier and because it is more comfortable. When faced with the need to recalibrate our understanding of a situation, it is a natural response to default to the comfort of what we know, resisting expending the cognitive effort required to embrace a more expansive vision. Rooted in our inherent aversion to uncertainty, we default to a tendency to avoid change, even when the alternatives present needed opportunities for improvement.

A ‘Sizeable’ Debate for the Courts

Although resistance to change is a fundamental aspect of our individual cognitive processes, its influence extends beyond our personal lives to the institutions that shape our society. In particular, an institution often seen as resistant to change (or perhaps that we are hesitant to see changed) is the Supreme Court of the United States. As the highest judicial body, the Court that plays a pivotal role in interpreting the law and shaping the course of the nation, seems set in stone.

Recently, the composition of the Court—in particular, the number of Justices serving on the bench—has begun to blossom as a topic of discussion. However, when examining questions about the Court’s makeup, we are faced with the very same cognitive resistance to change that permeates our individual circumstances. The current structure of nine Justices seems so deeply ingrained in our collective consciousness that it is both easy to overlook the fact that it hasn't always been this way, and difficult to picture it otherwise. To ensure the Supreme Court remains effective and relevant in a constantly changing world, we must be aware of our inherent predispositions for resisting change so that we can fairly and critically evaluate the potential merits and drawbacks of altering the Court's size.

More Justices, More Justice?

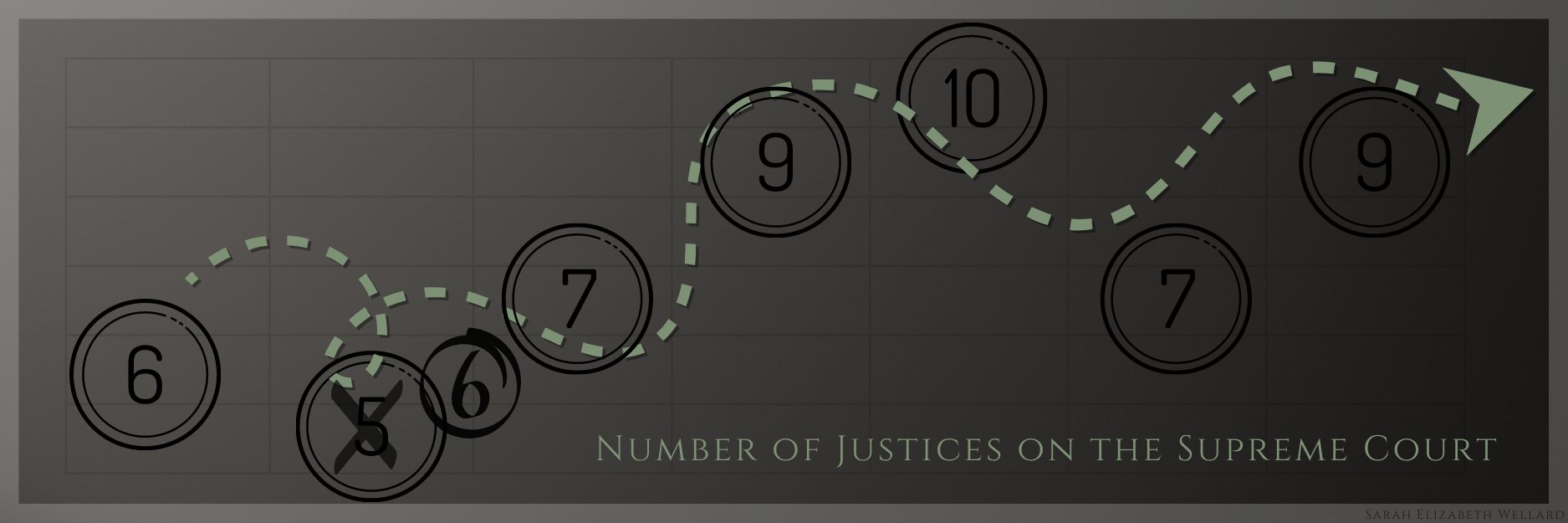

Though the Court has maintained a nine-Justice composition throughout all of our lifetimes, the number of Justices on the Supreme Court has actually fluctuated several times prior to settling on the current count. To better understand the dynamics of the Supreme Court’s membership, examining its historical context not only highlights the Court’s capacity to evolve, but also underscores its potential to change in the future:

In 1789, Congress, fulfilled its Constitutional obligation to establish a Supreme Court, which they initially decided should consist of six members: one Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. However, the history of the Supreme Court's expansion has not been linear. In 1801, Congress reduced the number of Justices from six to five, but the following year repealed the act, returning to a six-member court. Six years later, Congress expanded the Court to include a total of seven Justices. Another 30 years later, and prompted by the establishment of additional federal circuits, the Court’s size was once again increased, this time to a total of nine Justices. During the Civil War, the Court expanded to ten Justices, but in the post-Reconstruction era the number of Justices was reduced to seven. Most recently, in 1869, and again in response to the growing number of federal circuits, the Court’s size was increased to nine Justices—a number that has remained constant ever since.[4]

History shows us that even the most seemingly entrenched pillars of our society have undergone transformation and evolution. In its first 80 years alone, the Court experienced seven changes to its size. Notably, each time the composition of the Court changed, it did so in direct response to the circumstances and legal landscape of its era, underscoring the Court's capacity to adapt and respond to the needs of the nation. However, for over 150 years, the Court's size has remained constant, prompting the current conversation about whether it is time for an update. Today, the ongoing dialogue surrounding the Court's size reflects the shifting dynamics and demands of our society, inviting a critical examination of its current configuration.

Supreme Makeover: The Case for a Bigger Bench

From a purely non-political standpoint, there is a compelling argument for increasing the number of Supreme Court Justices from nine to 13, in order to align with the current number of federal circuit courts. Currently, each of the thirteen federal circuit courts is assigned one Supreme Court Justice who, alone, considers certain specialized appeals (for example: emergency requests) from their respective circuits, while a case is still pending in a lower court. However, at present, there are 13 federal judicial circuit courts, but only nine Justices. This means that the disparity between the number of Justices and the number of circuits results in situations where individual Justices are assigned to multiple circuits.[5] Expanding the Court to 13 Justices would ensure that each federal circuit court is represented by an assigned Justice dedicated solely to the jurisdiction it serves. As a result, an expanded Supreme Court would more accurately represent the diverse geographical and jurisdictional areas of the United States—potentially ensuring more equitable representation for each circuit when the Court makes decisions that affect the entire nation. A larger Court also allows for a broader range of backgrounds, experiences, and legal philosophies, leading to a richer and more nuanced interpretation of the law; accordingly, an expanded Court may be better equipped to handle emerging legal challenges. Finally, an increase to the size of the Court may ameliorate concerns regarding the Court’s ideological balance and reduce the perception of the Court as a politicized institution. With a larger bench, the influence of individual political appointments would be diluted, minimizing the potential impact of the views of any single justice on the Court's overall decision-making. The same would hold true in the event that a Justice or Justices need to recuse themselves from a case for personal reasons: the absence of any one person’s perspective would have less significant impact. The increased representation, wider array of perspectives, and diminished influence of political ideologies, would only serve to foster public confidence, ultimately strengthening the Court's effectiveness.

Closing Arguments for an Evolving Supreme Court

The prospect of expanding the Supreme court is a contentious and highly debated one, and is not without its share of challenges and complications. Concerns include things like the potential for increased political polarization and gridlock in the confirmation process (particularly in initially filling the additional four seats). Expanding the Court might also lead to more crowded and complex interactions during oral arguments and deliberations, potentially affecting the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the judicial process. Additionally, by deemphasizing the voice of the Justices as individuals, we risk weakening the accountability held by each Justice. As with any proposed reform, consideration for expanding the court should thoroughly assess both the upshots and potential consequences of implementing such a change.

The Supreme Court holds a vital role as the highest judicial body in the United States, entrusted with interpreting the law and safeguarding the principles of justice. It is crucial that the Court operates in a manner that promotes public confidence, ensuring its legitimacy and preserving its ability to uphold the rule of law. Yet, large scale polling reports that public opinion of the Supreme Court is at the lowest it has been in fifty years.[6] This is a terrifying outlook for democracy. If the public loses confidence in the legitimacy of the Supreme Court, the consequences will be far-reaching, further eroding trust in the judicial system and undermining the Court's authority and ability to effectively fulfill its constitutional duties. A weakened judiciary compromises the checks and balances necessary for a functioning democracy, potentially leading to a breakdown of the rule of law, diminished protection of individual rights, and an erosion of public trust in the democratic process as a whole.

Perhaps a change is in order.

The hope is that by carefully examining the potential outcomes of expanding the Supreme Court, we may find ways to support the Court as it navigates a world that refuses to stand still...despite our will for it to do so.

To be clear, any decision to expand the court should be as far removed as possible from political influence. Instead, our objective should be to uphold and preserve the integrity of one of the fundamental pillars of the democratic system: the impartiality and credibility of the judiciary. By contemplating the prospect of expansion and working towards better understanding the nuances of how the Court shapes our collective experience, we might breathe new life into our judiciary, reaffirming its legitimacy and bolstering its ability to safeguard the principles upon which our nation was founded. The hope is that by carefully examining the potential outcomes of expanding the Supreme Court, we may find ways to support the Court as it navigates a world that refuses to stand still...despite our will for it to do so.

[1] Metaphor courtesy of Pashler, H., & Johnston, J. C. (1998). Attentional limitations in dual-task performance. In H. Pashler (Ed.), Attention (pp. 155–189). Taylor & Francis.

[2] Zipf, G. K. (1949). Human behavior and the Principle of Least Effort: An Introduction to Human Ecology. Addison-Wesley Press

[3] For more on this concept, see: Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[4] Although the size of the Court has not changed since 1869, proposals to alter its composition again arose in the 1930s, though those changes were never actually implemented. Frustrated by the Court's rejection of several New Deal policies, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed a court-packing plan to expand the Court and appoint Justices aligned with his views. However, in order to prevent this from happening, Justice Owen Roberts (who had previously sided with the Court's conservative faction in striking down New Deal legislation) altered his position on key New Deal legislation, aligning with the majority and effectively preventing President Franklin D. Roosevelt's court-packing plan—thus preserving the Court's traditional nine-justice composition. This is now known as the “Switch in Time that Saved Nine.” I love a good pun.

[5] 28 U.S.C. §42

[6] Statistics courtesy of the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/trends?category=Politics&measure=conjudge